I don’t preach often, but I did once this summer. I also don’t have much time for blogging new material lately, so I thought I’d post this. – CW

———————————————————————-

Caldwell Free Methodist Church

12 July 2015 – Year B – 8th Sunday after Pentecost – Ordinary Time Proper 10

Amos 7:7-17 // Mark 6:14-29

Imagine you’re just taken a clerical job in an insurance firm. As you begin cataloging claims, you notice that many of them include payouts far lower than the policies promise. That’s not too strange, you suppose, because insurance companies need to be very specific in their policies or they won’t survive. But then you start to notice a pattern… the names. Your company has a wide diversity of clients, but the policies that have lower payouts all have names on them like, “Juana María Martínez,” “Julio García,” or “Ernesto Rodriguez.” You remember Julio. He came in last week. In halting English, through a dazzling smile, he told you about his family—his wife Emilia and his three little girls. He showed you pictures. You begin to wonder if someone is discriminating against Latino people, maybe taking advantage of poor English skills, in order to cut corners on policy payouts. You go through the documents again. Your heart sinks as on every one you see the same signature approving the short payout—your immediate supervisor’s. Your conscience tells you that you should confront your supervisor; this injustice needs to be righted. But at the same time, you know that speaking up could cost you your job.

If you relate to this scenario, you’re in good company. The Bible is full of stories where God sends a lowly person to confront a high-status person. That’s almost the definition of what a prophet is. Prophets speak uncomfortable truths to people in positions of religious and political power. Remember Samuel confronting Saul to tell him that he was rejected as king of Israel? Remember the prophet Nathan confronting David with accusations of murder and wife-stealing? Remember Elijah’s challenge to Ahab for worshiping the foreign god Baal? So, too, with Amos and John the Baptist.

God sends Amos, the shepherd and tree trimmer from Judah, to prophesy to Israel under king Jeroboam. This is Israel’s second king named Jeroboam and, by worldly measures, he’s wildly successful. He ruled for 41 years and expanded Israel’s borders, recovering Damascus and Hamath, cities previously lost to other nations (2 Kings 14). Israel prospered during his reign, but the author of 2 Kings reckons the quality of his kingship in rather different terms: “He did what was evil in the sight of the Lord; he did not depart from the sins of Jeroboam son of Nebat” (14:23), which is to say this Jeroboam continued to lead the people of Israel in idolatrous worship just as the first Jeroboam had done: golden calves set up in the cities of Dan and Bethel (1 Kgs 12:28-33). But that isn’t all. While Israel prospered as a whole during Jeroboam’s reign, the rich oppressed the poor, violence abounded, and the courts were corrupt. The earlier chapters of Amos describe how, under Jeroboam, Israel combines the sins of idolatry and oppressive injustice toward the vulnerable:

Amos 2:6 – “They sell the righteous for silver, and the needy for a pair of sandals; they who trample the head of the poor into the dust of the earth, and push the afflicted out of the way”

Amos 3:10 – “They do not know how to do right, says the Lord, those who store up violence and robbery in their strongholds.”

Amos 4:1-5 Speaks about the rich women of Israel as “cows of Bashan… who oppress the poor, who crush the needy” without a thought for how their plenty plunges others into poverty. Because Israel doesn’t repent when it suffers from plague, famine, drought and war, Amos prophesies the consequences in chapter 5:

“Therefore, because you trample on the poor and take from them levies of grain, you have built houses of hewn stone, but you shall not live in them: you have planted pleasant vineyards, but you shall not drink their wine. For I know how many are your transgressions, and how great are your sins—you who afflict the righteous and take a bribe, and push aside the needy in the gate. Therefore, says the Lord, the God of hosts, the Lord: In all the squares there shall be wailing, and in all the streets they shall say, “Alas, alas!” They shall call the farmers to mourning, and those skilled in lamentation, to wailing; in all the vineyards there shall be wailing, says the Lord.”

While Israel oppresses its poor, no amount of song-singing or sacrifice will make up the difference, so says the Lord:

“I hate, I despise your festivals, and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies. Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings I will not accept them, and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals, I will not look upon. Take away from me the noise of your songs: I will not listen to the melody of your harps. But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”

The cure for Israel’s idolatry and oppression of the poor is a flood of righteousness and justice; the true worship of God embodied in social justice. If Israel does not turn away from its idolatry and oppression and do justice instead exile awaits. A foreign nation will swoop in to oppress Israel, divide up its land, and carry its people into exile.

No wonder Amaziah, the priest at Bethel, tells Jeroboam about Amos, “the land is not able to bear all his words,” and tries to get rid of him. Remember, Bethel is the site of one of Jeroboam’s idolatrous sanctuaries as well as his palace. Amos has gone to the heart of Israel to speak to the seat of power because, historically, as goes the king, so goes the rest of Israel. Israel is sunk into idolatry in the first place because of the first Jeroboam, and this Jeroboam has carried on that same program of idolatry and oppression.

Imagine being Amos. A vulnerable nobody, a shepherd and tree-trimmer, he probably knows a good deal about exploitative labor and struggling to make ends meet. Moreover, being from Judah, he’s from the land just to the south that Israel views like a bullying older brother—worse, in some ways, than if Amos were from an actual foreign country. And yet God sent him to prophesy against Israel’s oppressive practices. It’s a precarious position for him. Israel’s kings often did not hesitate to torture, kill, or try to kill the prophets who spoke to them of their sins. Just goes to show that sometimes, being faithful to God—especially by standing up to the powerful who are crushing others—can be costly. It can cost you your life.

So it did John the Baptist. In Mark’s Gospel, John is the first character we meet, and he has a prophetic identity from the start. He is the messenger God promised in Malachi 3:1 to “prepare the way.” He is “voice crying out in the wilderness,” from Isaiah 40, “prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.” These words are meant to prepare exiles for return. They go right along with “Comfort, comfort my people,” and “Speak tenderly to Jerusalem” and “Every valley shall be lifted up, every mountain and hill made low, the uneven ground shall become level, and the rough places a plain. Then the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all people shall see it together.”

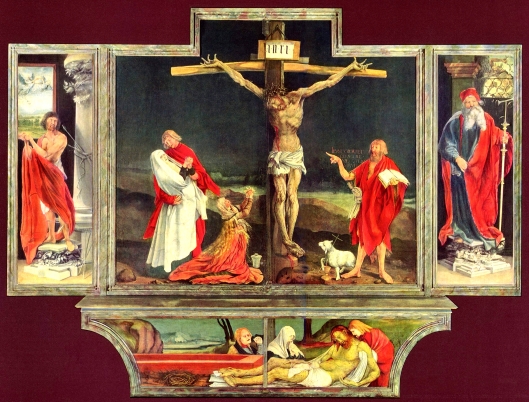

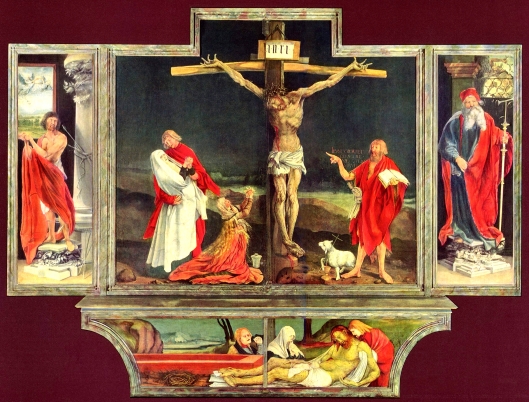

Isenheim Altarpiece, Matthias Grünewald

John prepares the people for the revealing of God’s glory, the fully alive glory of God—embodied in Jesus. How does he do it? Like every prophet before him, by calling the people to repentance. John baptizes people for repentance and forgiveness of sins, telling them to look for the one who is coming after him, who is more powerful. John points to Jesus. And turning to Jesus requires repentance—from every sin whether personal, communal, social, or systemic.

Mark mentions nothing more about John the Baptist before the account of his arrest and death. He writes even less about Herod, but it’s clear Herod’s no hero. Although he’s technically a Jewish king, Herod was in Rome’s pocket. The only times we see him in Mark, he is arresting and killing John the Baptist, or Jesus is warning his disciples to steer clear of Herod’s patterns of thought and life. Moreover, Herod’s henchmen are always conspiring with the Pharisees, trying to trap Jesus into speaking blasphemy against God or revolt against the Romans. Herod is no hero.

In this story, we learn that John the Baptist called him out for a particular sin—taking his brother Phillip’s wife, Herodias, as his own. Herod has apparently been able to ignore John’s message about every other sin he might be committing. Mark writes, “when Herod heard John, he was greatly perplexed, but he liked to listen to him” (v. 30). To Herod, John is mostly the crazy man scantly clad in camel hair and a leather belt, raving about repentance and a more powerful messenger who would come after him. John is usually just the entertaining madman—except when he tells Herod it’s not lawful for him to have his brother’s wife. That’s personal. Obviously Herod was not the only one in his court whom John made uncomfortable, and Mark tells us Herod was protecting John from Herodias, the wife he wasn’t supposed to have. But two facts are inescapable: 1) Herod had John arrested so that he was easily to hand to behead, and 2) Herod had the final say in John’s death. It was too convenient; John was in Herod’s prison, so when push came to shove, it was easy to give the order.

The fact is, if you are going to speak to people in power about their sins, you have to be prepared for this sort of cost. In the Bible, the prophets seem well aware of that, but they obey God anyway. Sometimes, such speech is exactly what faithfulness to God demands. If you see abuse of power, exploitation of the vulnerable, or policies that make the poor poorer you may be called to speak with a prophetic voice.

Then again, maybe not. Remember that God sent Amos to Israel—not a foreign country or a historic enemy, but a people who share his heritage of life with the Lord God. Jeroboam is king of Israel. Amos calls Israel and Jeroboam back to life with God; you can’t be called back if you were never there. Amos brings a message to insiders who have gone astray; the same is true of John the Baptist. Herod may be deep in Rome’s pocket, but John refers to the Jewish law when he says, “it is unlawful for you to have your brother’s wife.” Maybe we’re not the prophet. Maybe we’re the leader and people gone astray together. Maybe we’re like the rich women of Israel, buying our clothes without considering the sweatshop workers who make them. Maybe we, too, participate in systems of exploitation. You know, a few months back, Pastor Jim mentioned a local employer who hired illegal workers and then called INS just before payday. I wondered what product that employer is selling, and whether we’re buying it. If we are, will God look on our Sunday services with disgust, our sharing communion as mockery, and hear our worship songs as an assault on the ears? As James put it, “Faith without works is dead.” Maybe we’re Herod. Maybe we’re Jeroboam. Maybe we’re wicked Israel. If we are, and we want to be God’s people, we must listen to the prophets among us.

So let us remember that the prophets may well speak from a place of vulnerability, of powerlessness, or obscurity. Prophets may sound or look crazy—may not seem like credible, sane people. If you’re a prophet you may be angry, distressed, or extremely shy but unable to stay silent any longer exactly because you yourself have suffered the very abuses you see the powerful perpetrating:

- The strongest advocates I know for victims of sexual assault are survivors themselves.

- The most vocal advocate I know for veterans suffering the costs of war was himself a soldier in Iraq.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke out against systemic racism and violence from his own experience, but he didn’t do so only for himself. He did it for the good of everyone—regardless of race, both victims and perpetrators—because he knew that everyone suffers in such a system.

Sometimes prophets speak in the hope that others won’t have to suffer what they have suffered.

If you are a prophet, I hope you find the courage to speak. And if you are called to speak to us, may God grant us the humility to hear you. Let us “prepare the way of the Lord,” so that the glory of God alive in Jesus may be revealed in us. Amen.